یہ خلیل کی سب سے بہترین کتاب سمجھی جاتی ہے جس میں اس نے زندگی مختلف پہلوؤں پر اپنے مخصوص انداز میں بات کی ہے. یہ انتہائی دلچسب اور گہری کتاب ہے جسے ایک صدی بعد بھی اتنی ہی پذیرائی حاصل ہے جتنی پہلی نسلوں میں ملی.

🖊شادی:

Anyone learning about Islam from the headlines alone might think it was a faith powered by violence, inflexible laws, and sexism. In Nigeria, the extremists of Boko Haram kidnap schoolgirls to use as sex slaves and suicide bombers. A manifesto distributed by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) allows girls to marry at age nine and states that women should work outside the house only in “exceptional circumstances.” It’s not only extremist movements that treat women as second-class citizens, but also Western allies in the fight against them. Whether it’s Saudi Arabia, where women are banned from driving, or Egypt, where a husband can divorce his spouse without grounds or going to court, options denied to his wife, most Muslim countries run on the premise that men have a God-given authority over women.

But Muslim women are fighting back. While despotic governments and extremists battle for power, Islamic scholars, community activists, and ordinary Muslims are waging a peaceful jihad on male authority, demanding what they say are God- given rights to gender equality and justice.

From Cambridge to Cairo to Jakarta, women are going back to Islam’s classical texts and questioning the way men have read them for centuries. In the Middle East, activists are contesting outdated family laws based on Islamic jurisprudence, which give men the power in marriages, divorces, and custody issues. In Europe and the United States, women are chipping away at the customs that have had a chilling effect on women praying in mosques or holding leadership positions. This winter, the first women-only mosque opened in Los Angeles.

These efforts are localized and diverse. But all are part of the multi-faceted struggle in today’s Islamic world between fundamentalist rigidity and a pluralist, inclusive faith. “We represent hope, hope for the future, and for what it means to be Muslim today,” said Zainah Anwar, director of the global Muslim women’s organization Musawah—Arabic for ‘equality’—at a recent conference in London. “Do we want to choose ISIS? Or do we want to choose musawah?”

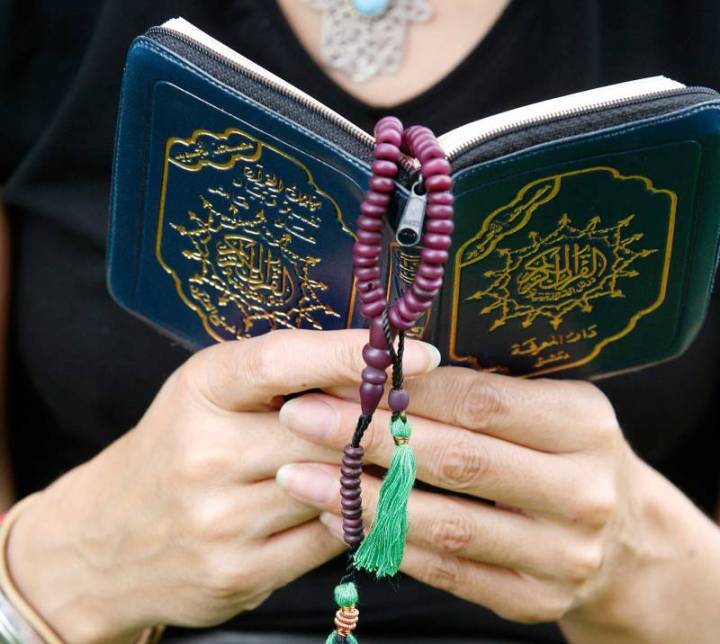

Anwar was addressing a packed auditorium at the University of London’s School of Oriental and Asiatic Studies for the release of a powerful new weapon for Islamic gender warriors: a book examining how a single verse in the Quran became the basis for laws across the Islamic world asserting Muslim men’s authority—and even superiority—over women. In Men in Charge?, scholars tackle what Musawah has dubbed “the DNA of patriarchy” in Islamic law and custom: the thirty-fourth verse in the fourth chapter of the Quran, among the most hotly debated in the Islamic scripture. The English translations of the verse vary, but one popular one conveys the mainstream takeaway: “Men are in charge of women, because Allah hath made the one of them to excel the other, and because they spend their property [for the support of women.]”

For centuries, male jurists have cited 4:34 as the reason men have control over their wives and the female members of their family. When a wife doesn’t want to have sex, but feels she should submit to her husband, this sense of duty derives from the concept of qiwamah—male authority—derived from Verse 4:34. When a Nigerian wife reluctantly has to agree to her husband taking a second or third wife, this is qiwamah in action, notes the book. The concept of qiwamah “is one of the most flagrant misconceptions to have shaped the Muslim mind over the centuries,” Moroccan Islamic scholar Asma Lamrabet writes. “It assumes that the Quran has definitively decreed the absolute authority of the husband over his wife, and for some, the authority of men over all women.”

While the overall message of the Quran is unchanging, say Muslim reformers, new generations must find their own readings of the sacred texts. As it stands, Islamic fiqh, or jurisprudence, was largely forged during the medieval period, when women’s roles and the concept of marriage and male authority were very different. Why, they ask, should the way that 10th-century Baghdadi men read the Quran dictate the rights of a 21st-century woman? To the reactionaries who charge that these reformers are deviating from Islam, Islamic feminists point out that there is a difference between Islamic jurisprudence—a man-made legal scaffolding developed for the specific conditions of medieval Muslim life—and the divine law itself, which is eternal, unchanging and calls for justice. It’s not the Quran they question, but how particular interpretations of it have hardened into truth. “The problem has never been with the text, but with the context,” legal anthropologist Ziba Mir-Hosseini told the Musawah seminar.

For activists battling for reform of discriminatory laws, there’s hope—at least on paper. In 2004, Morocco redrafted its family law code to state that husbands are no longer the heads of the household and marriage is a matter of “mutual consent” between husband and wife. But even ten years on, “the results are very weak, because of the mentality here,” Lamrabet conceeded. She once addressed a group of male religious scholars about equality in the Quran. “It was like an inquisition,” she recalled wryly. “Everybody was standing up, and saying, Qiwamah [male authority] is here to demonstrate that there is no musawah [equality] in our religion!”

Not as it’s practiced in most places now. But the mood at Musawah is optimistic. At the United Nations, Musawah’s Anwar reminded the Commission on the Status of Women that Muslim women don’t need to choose between Islam and equal rights; while 4:34 is invoked by sexists, there are many more passages calling for justice, and a sound Quranic tradition saying that all humans are equal as God’s creations. In London, Anwar asked the crowd of Muslim women a fundamental question: “If we are equal before the eyes of God, why not before the eyes of men?”

Article was written by Carla Power and originally published in Time Magazine in 2015.

By Enrique Lin Shiao

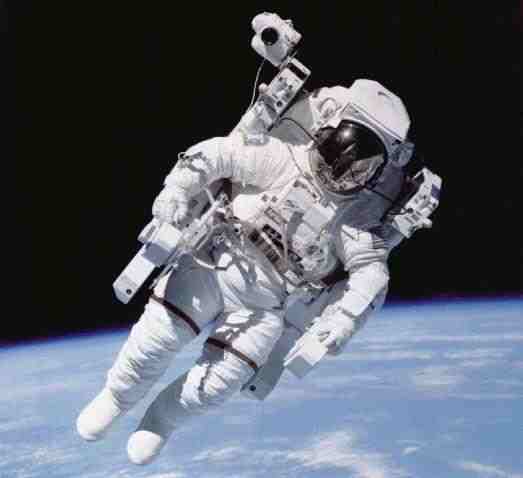

Growing up in Costa Rica in the early 90s, I remember seeing Costa Rican astronaut Dr. Franklin Chang Diaz in newspapers, televisions and billboards across the country. Seeing him in the media, as he floated around a space ship and tinkered with its mechanics, inspired my generation to believe nothing is out of our reach and motivated many, including myself, to pursue a career in science. Ultimately, I discovered my passion did not lay in aeronautics but rather in understanding the rules that govern biological systems and in particular the human body. However, without a clear role model paving the way for me, I am not sure I would have pursued a career in this field.

Science has given me the opportunity to move across four countries and meet scientists from all around the world. For many of them, a clear role model has been fundamental in their decision to pursue a career in science. Particularly for people in developing countries or minorities and people from low income communities in developed countries, a lack of representation in science often makes it hard to understand what steps are needed to pursue a career in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). It can also be very discouraging when you cannot identify people from your country or communities working in the jobs or fields you are passionate about.

Beyond strong role models, there are many ways in which scientific interest in developing countries can be expanded. Together with my colleague Kevin Alicea Torres, we recently started a podcast titled “Caminos en Ciencia” (Pathways in Science). Here, we interview Latin American scientists at different career levels (undergraduate, graduate, postdoctoral, professors, industry and government) working across the world, with the hope of making scientific careers more tangible and accessible for people within our region. Through these interviews we have learned a lot about how developing countries can develop scientists and I summarise some of the most valuable lessons here.

Starting early is crucial. In the United States, programmes such as “Upward Bound Math Science” aim to provide early exposure and training in STEM fields to low-income and first-generation college students. Through easy experiments, high school students learn about the scientific process and what steps are required to pursue a career in a STEM field. Similar projects have grown in developing countries; however, there are still many opportunities to further expand these programmes, for example, universities in developing countries could form stronger partnerships with local high schools, to expose students early on to laboratory work and scientific thought. Additionally, non-profit organisations can fill many gaps. Science Slam Festival Uruguay, an event sponsored by UNESCO, brings science to children and adults through art and interactive activities.

Science camps, high school internships, stargazing events, science pub talks, and kindergarten programmes can be implemented at low cost to expose people from different age groups to science. A great example is “Integrating Science in the Philippines” a group started by Filipino high school students. Co-founder Paulo Joquiño explains, “we identified a wide gap in STEM training between science high schools and other schools in the Philippines and thus founded ISIP to try to bridge this gap by bringing scientific opportunities and lab exposure to underprivileged high school students all across the country.”

In many developing countries, the quality in educational training in STEM differs greatly between public and private schools. To counteract this, public vocational and technical schools have emerged as a great opportunity to capture and grow scientific talent. Dr. Darel Martinez, from the Center of Molecular Immunology (CIM) in Cuba, attributes part of Cuba’s strength in forming scientists to vocational high schools that emerged in the early seventies. “The focus of these institutions has been to identify students with high affinity to STEM fields early on and provide them with strong scientific training throughout high school” explains Darel. “This has allowed the country to achieve important scientific breakthroughs while working with relatively lower resources. One such discovery is the lung cancer vaccine CIMAvax,” he adds.

Role models play a key role in sparking scientific interest. Role models can be family members, scientists, engineers, teachers, neighbours, friends, etc. “I had no concept of what being a career scientist meant until a friend of mine mentioned it to me in college” says Mariel Coradin, a Dominican scientist who is currently working on her PhD at the University of Pennsylvania. “Without the mentorship of Prof. Gary Toranzos, with whom I worked with during my undergraduate studies, I wouldn’t have further developed my interest in science and I wouldn’t be where I am today,” she adds, underscoring the importance of role models and mentors in developing scientists.

Limited funds for science and research can be a strong deterrent towards pursuing a career in STEM fields. Developing countries often must allocate their funds to other priorities, making it challenging to fund basic research. However, many alternative mechanisms have emerged to allow science to be funded in these places. In Costa Rica, the Central American Association for Aeronautics and Space tapped into crowdfunding to send the region’s first satellite into space. The satellite bearing the name Irazú in honour of one of Costa Rica’s main volcanoes was launched earlier this year. Further, international collaborations are an excellent way not only to fund but also to advance science. “We are part of an international collaboration funded by the Medical Research Council that includes Costa Rica, Scotland, Nepal and Malawi. Our aim is to combine genetic and epidemiological risk factors to understand how they influence mental health,” says Dr. Henriette Raventós Vorst from the Center for Cellular and Molecular Biology at the University of Costa Rica. These international collaborations not only allow for funds to reach countries with less resources but also provide novel and unique scientific insight to advance scientific fields. Non-profit organisations, public-private partnerships and start-ups are also alternative ways to fund science. “At CIM in Cuba we fund a great part of our research through ciclo cerrado (closed cycle), this is a strategy in which we sell kits, compounds, vaccines and other products that we develop to fund new research in our institution,” explains Dr. Darel Martinez.

Lastly, to develop scientists in developing countries a concerted effort is also required from media and government to promote science. Sections in the newspaper or in daily TV news highlighting different national and international scientists, as well as their scientific findings are key to bringing science closer to the public and making scientific careers more tangible. Further, highlighting science as a tool for development is crucial. In Costa Rica, the government recently announced that they would work together with astronaut Dr. Franklin Chang Diaz to introduce hydrogen buses in an effort to become carbon neutral by 2021. It is not the first time that the Costa Rican government has worked with scientists to provide novel technological solutions to our country’s challenges.

I continue to follow and feel inspired by the portrayal of scientists in Costa Rican media, and it is very encouraging to see how the astronaut that inspired me to follow a career in science can continue to inspire new generations of scientists in Costa Rica.

To conclude, while many of these lessons are crucial for developing scientists in developing countries, most of them can also be applied to spark scientific interest in low income and underprivileged communities in developed countries. Promoting scientific diversity, international collaborations and developing scientists worldwide not only provides means to allow communities and countries to further develop and prosper but also enriches and advances science by introducing novel ways of thinking, ideas and solutions.

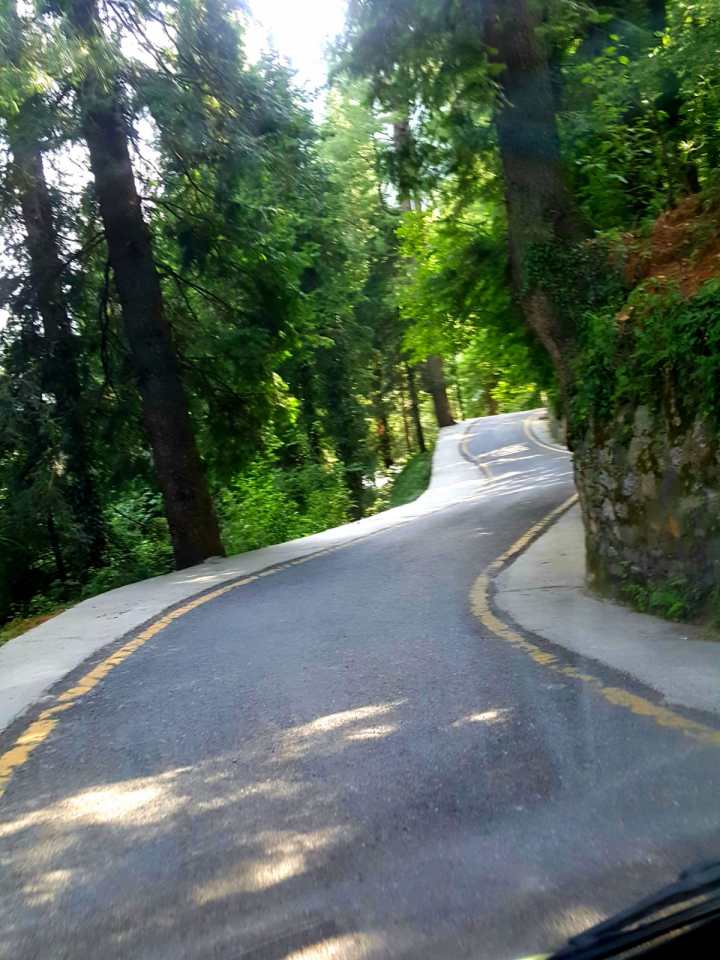

Mukshpuri is about 2800m (9200ft) mountain in Nathia Gali and is the second highest peak in the region after Mirajani (3000m, 9800ft). When I was in my high school in late 90s one of my uncle and his friends went to Mukshpuri. Ever since then I was planning to go there as well but due to study and work abroad I never had an opportunity to hike around thick pine forest of Galiyaat. Recently, I saw several social media blogs and Facebook posts and tweets about Mukshpuri. Being local and climatized for several weeks in Abbottabad and Biran Gali, I finally decided to go there.

Ariel view of Mukshpuri peak. Downhill Dunga Gali bazar can be seen. Picture taken with DJI Spark.

Ariel view of Mukshpuri peak. Downhill Dunga Gali bazar can be seen. Picture taken with DJI Spark.

Whole Galiyat generally and Nathia Gali and surroundings particularly are accessible throughout the year though recommended season for Mukshpuri is between April and October. Galiyat receives massive snow during peak winters and therefor I would avoid trekking during December-March. My favourite time is either May-June or Sep-Oct. During July-August you may have poor visibility due to clouds. If you are traveling with your own car it takes about 2 hours from Abbottabad, road is in excellent condition but often gets slippery due to rain and have dangerous turns. Some turns between Abbottabad and Nathia Gali are very notorious and have taken several lives. Drive carefully without burning your butts! You can also drive directly from Islamabad, leave early morning, park in Dunga Gali. There is a newly built road (about 1 Km) upwards from Dunga Gali, you should drive up there. This will save your calories. There is no free parking but you can get one with Rs 200-250. At the start of trek you need to pay small entry fee.

This trek is very well maintained and track is not very steep. Total one way distance is 3 Km. Depending on your speed and stamina trekking time varies. We hiked up in 70mins with two 5min breaks. Taking small children is not recommended unless you can carry them up. We dared to take our 2 year old daughter with us!!! I recommend starting the trek no later than 1:00 PM, earlier is better.

Mukshpuri is very photogenic place. On a clear day (usually in May-June) you can spot several villages of districts Abbottabad, Nathia Gali, Ayubia, Mirajani, Muree, Kahota, and even AJK including river Jhelum. Place is spectacular for photography and even walk (if you can do it after long hike). Camping is possible but I am not sure if it is allowed by wildlife department as the area is surrounded by thick forest and there is risk of wild animals. If you plan to camp at the top take at least 8-10 people and double check the forecast.

This is a highly recommended place for young people, groups, families and couples. The peak is very similar to Seri-Paye in the Shogran region of KPK with much more convenient and accessible track. KPK tourism and wildlife department has maintained the whole region very well. There are several litter boxes and even staff taking care of plastic and food waste. Chacha Bashir is one of the locals hired by the wildlife department to keep Mukshpuri clean for you. I hope you will maintain the civic sense and responsibility and protect the environment for your coming generations. Have a wonderful trek!!!!

ISLAM, THE WEST, AND THE FUTURE

By Arnold J Toynbee

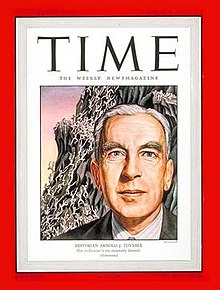

(This is a chapter of a book by Arnold J Toynbee, Civilization on Trial, published by Oxford University Press 1948. Toynbee’s chapter is reproduced in its entirety below. The introduction to the author, the headings and accentuation of some text into bold letters has been added by Alislam-eGazette editor.)

The essence of Toynbee meta-history is that civilizations thrive and survive on the basis of their ideas. As Muslims polish their ideas and their pens and realize that they do not have a sword suitable to this day and age, they will inherit the future, and unite mankind in a universal brotherhood.

Alislam-eGazette editor

INTRODUCTION TO ARNOLD TOYNBEE

Encyclopedia Britannica online has the following to say about Toynbee:

“Arnold J Toynbee was an English historian whose 12-volume A Study of History (1934–61) put forward a philosophy of history based on an analysis of the cyclical development and decline of civilizations that provoked much discussion.

Toynbee was a nephew of the 19th-century economist Arnold Toynbee. He was educated at Balliol College, Oxford (classics, 1911), and studied briefly at the British School at Athens, an experience that influenced the genesis of his philosophy about the decline of civilizations. In 1912 he became a tutor and fellow in ancient history at Balliol College, and in 1915 he began working for the intelligence department of the British Foreign Office. After serving as a delegate to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 he was appointed professor of Byzantine and modern Greek studies at the University of London. From 1921 to 1922 he was the Manchester Guardian correspondent during the Greco-Turkish War, an experience that resulted in the publication of The Western Question in Greece and Turkey (1922). In 1925 he became research professor of international history at the London School of Economics and director of studies at the Royal Institute of International Affairs in London.

Toynbee began his Study of History in 1922, inspired by seeing Bulgarian peasants wearing fox-skin caps like those described by Herodotus as the headgear of Xerxes’ troops. This incident reveals the characteristics that give his work its special quality—his sense of the vast continuity of history and his eye for its pattern, his immense erudition, and his acute observation.

In the Study Toynbee examined the rise and fall of 26 civilizations in the course of human history, and he concluded that they rose by responding successfully to challenges under the leadership of creative minorities composed of elite leaders. Civilizations declined when their leaders stopped responding creatively, and the civilizations then sank owing to the sins of nationalism, militarism, and the tyranny of a despotic minority. Unlike Spengler in his The Decline of the West, Toynbee did not regard the death of a civilization as inevitable, for it may or may not continue to respond to successive challenges. Unlike Karl Marx, he saw history as shaped by spiritual, not economic forces.

While the writing of the Study was under way, Toynbee produced numerous smaller works and served as director of foreign research of the Royal Institute of International Affairs (1939–43) and director of the research department of the Foreign Office (1943–46); he also retained his position at the London School of Economics until his retirement in 1956. A prolific writer, he continued to produce volumes on world religions, western civilization, classical history, and world travel throughout the 1950s and 1960s. After World War II Toynbee shifted his emphasis from civilization to the primacy of higher religions as historical protagonists. His other works include Civilization on Trial (1948), East to West: A Journey Round the World (1958), and Hellenism: The History of a Civilization (1959).

Toynbee has been severely criticized by other historians. In general, the critique has been leveled at his use of myths and metaphors as being of comparable value to factual data and at the soundness of his general argument about the rise and fall of civilizations, which relies too much on a view of religion as a regenerative force. Many critics complained that the conclusions he reached were those of a Christian moralist rather than of a historian. His work, however, has been praised as a stimulating answer to the specializing tendency of modern historical research.”1

According to Wikipedia:

“Arnold Joseph Toynbee CH (April 14, 1889 – October 22, 1975) was a British historian whose twelve-volume analysis of the rise and fall of civilizations, A Study of History, 1934-1961, was a synthesis of world history, a meta-history based on universal rhythms of rise, flowering and decline, which examined history from a global perspective.

Toynbee’s ideas and approach to history may be said to fall into the discipline of Comparative history. While they may be compared to those used by Oswald Spengler in The Decline of the West, he rejected Spengler’s deterministic view that civilizations rise and fall according to a natural and inevitable cycle. For Toynbee, a civilization might or might not continue to thrive, depending on the challenges it faced and its responses to them.

Toynbee presented history as the rise and fall of civilizations, rather than the history of nation-states or of ethnic groups. He identified his civilizations according to cultural or religious rather than national criteria. Thus, the “Western Civilization”, comprising all the nations that have existed in Western Europe since the collapse of the Roman Empire, was treated as a whole, and distinguished from both the “Orthodox” civilization of Russia and the Balkans, and from the Greco-Roman civilization that preceded it.

With the civilizations as units identified, he presented the history of each in terms of challenge-and-response. Civilizations arose in response to some set of challenges of extreme difficulty, when “creative minorities” devised solutions that reoriented their entire society. Challenges and responses were physical, as when the Sumerians exploited the intractable swamps of southern Iraq by organizing the Neolithic inhabitants into a society capable of carrying out large-scale irrigation projects; or social, as when the Catholic Church resolved the chaos of post-Roman Europe by enrolling the new Germanic kingdoms in a single religious community. When a civilization responds to challenges, it grows. Civilizations declined when their leaders stopped responding creatively, and the civilizations then sank owing to nationalism, militarism, and the tyranny of a despotic minority (see mimesis). Toynbee argued that “Civilizations die from suicide, not by murder.” For Toynbee, civilizations were not intangible or unalterable machines but a network of social relationships within the border and therefore subject to both wise and unwise decisions they made.

He expressed great admiration for Ibn Khaldun and in particular the Muqaddimah, the preface to Ibn Khaldun’s own universal history, which notes many systemic biases that intrude on historical analysis via the evidence.”

ZEALOTISM

In the past, Islam and our Western society have acted and reacted upon one another several times in succession, in different situations and in alternating roles.

The first encounter between them occurred when the Western society was in its infancy and when Islam was the distinctive religion of the Arabs in their heroic age. The Arabs had just conquered and reunited the domains of the ancient civilizations of the Middle East and they were attempting to enlarge this empire into a world state. In that first encounter, the Muslims overran nearly half the original domain of the Western society and only just failed to make themselves masters of the whole. As it was, they took and held North-West Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and Gallic ‘Gothia’ (the coast of Languedoc between the Pyrenees and the mouth of the Rhone); and a century and a half later, when our nascent Western civilization suffered a relapse after the breakdown of the Carolingian Empire, the Muslims took the offensive again from an African base of operations and this time only just failed to make themselves masters of Italy. Thereafter, when the Western civilization had surmounted the danger of premature extinction

and had entered upon a vigorous growth, while the would-be Islamic world state was declining towards its fall, the tables were turned. The Westerners took the offensive along a front which extended from end to end of the Mediterranean, from the Iberian Peninsula through Sicily to the Syrian ‘Terre d’Outre Mer’; and Islam, attacked simultaneously by the Crusaders on one side and by the Central Asian Nomads on the other, was driven to bay, as Christendom had been driven some centuries earlier when it had been compelled to face simultaneous attacks on two fronts from the North European barbarians and from the Arabs.

In that life-and-death struggle, Islam, like Christendom before it, triumphantly survived. The Central Asian invaders were converted; the Frankish invaders were expelled; and in territorial terms, the only enduring result of the Crusades was the incorporation in the Western world of the two outlying Islamic territories of Sicily and Andalusia. Of course, the enduring economic and cultural results of the Crusaders’ temporary political acquisitions from Islam were far more important. Economically and culturally, conquered Islam took her savage conquerors captive and introduced the arts of civilization into the rustic life of Latin Christendom. In certain fields of activity, such as architecture, this Islamic influence pervaded the entire Western world in its so-called ‘mediaeval’ age; and in the two permanently conquered territories of Sicily and Andalusia the Islamic influence upon the local Western ‘successor-states’ of the Arab Empire was naturally still more wide and deep. Yet this was not the last act in the play; for the attempt made by the mediaeval West to exterminate Islam failed as signally as the Arab empire-builders’ at tempt to capture the cradle of a nascent Western civilization had failed before; and, once more, a counter-attack was provoked by the unsuccessful offensive.

This time Islam was represented by the Ottoman descendants of the converted Central Asian Nomads, who conquered and reunited the domain of Orthodox Christendom and then attempted to extend this empire into a world state on the Arab and Roman pattern. After the final failure of the Crusades, Western Christendom stood on the defensive against this Ottoman attack during the late mediaeval and early modern ages of Western history-and this not only on the old maritime front in the Mediterranean but on a new continental front in the Danube Basin. These defensive tactics, however, were not so much a confession of weakness as a masterly piece of half-unconscious strategy on the grand scale; for the Westerners managed to bring the Ottoman offensive to a halt without employing more than a small part of their energies; and, while half the energies of Islam were being absorbed in this local border warfare, the Westerners were putting forth their strength to make themselves masters of the ocean and thereby potential masters of the world. Thus they not only anticipated the Muslims in the discovery and occupation of America; they also entered into the Muslims’ prospective heritage in Indonesia, India, and tropical Africa; and finally, having encircled the Islamic world and cast their net about it, they proceeded to attack their old adversary in his native lair.

This concentric attack of the modern West upon the Islamic world has inaugurated the present encounter between the two civilizations. It will be seen that this is part of a still larger and more ambitious movement, in which the Western civilization is aiming at nothing less than the incorporation of all mankind in a single great society, and the control of everything in the earth, air, and sea which mankind can turn to account by means of modern Western technique. What the West is doing now to Islam, it is doing simultaneously to the other surviving civilizations -the Orthodox Christian, the Hindu, and the Far Eastern world-and to the surviving primitive societies, which are now at bay even in their last strongholds in tropical Africa. Thus the contemporary encounter between Islam and the West is not only more active and intimate than any phase of their contact in the past; it is also distinctive in being an incident in an attempt by Western man to ‘Westernize’ the world-an enterprise which will possibly rank as the most momentous, and almost certainly as the most interesting, feature in the history even of a generation that has lived through two world wars.

Thus Islam is once more facing the West with her back to the wall; but this time the odds are more heavily against her than they were even at the most critical moment of the Crusades, for the modern West is superior to her not only in arms but also in the technique of economic life, on which military science ultimately depends, and above all in spiritual culture-the inward force which alone creates and sustains the outward manifestations of what is called civilization.

Whenever one civilized society finds itself in this dangerous situation vis-à-vis another, there are two alternative ways open to it of responding to the challenge; and we can see obvious examples of both these types of response in the reaction of Islam to Western pressure today. It is legitimate as well as convenient to apply to the present situation certain terms which were coined when a similar situation once arose in the encounter between the ancient civilizations of Greece and Syria. Under the impact of Hellenism during the centuries immediately before and after the beginning of the Christian era, the Jews (and, we might add, the Iranians and the Egyptians) split into two parties. Some became ‘Zealots’ and others ‘Herodians.’

The ‘Zealot’ is the man who takes refuge from the unknown in the familiar; and when he joins battle with a stranger who practises superior tactics and employs formidable newfangled weapons, and finds himself getting the worst of the encounter, he responds by practising his own traditional art of war with abnormally scrupulous exactitude. ‘Zealotism,’ in fact, may be described as archaism evoked by foreign pressure; and its most conspicuous representatives in the contemporary Islamic world are ‘puritans’ like the North African Sanusis and the Central Arabian Wahhabis.

The first point to notice about these Islamic ‘Zealots’ is that their strongholds lie in sterile and sparsely populated regions which are remote from the main

international thoroughfares of the modern world and which have been un- attractive to Western enterprise until the recent dawn of the oil age. The exception which proves the rule up to date is the Mahdist Movement which dominated the Eastern Sudan from 1883 to 1898. The Sudanese Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad, established himself astride the waterway of the Upper Nile after Western enterprise had taken ‘the opening up of Africa’ in hand. In this awkward geographical position the Sudanese Mahdi’s Khalifah collided with a Western power and-pitting archaic weapons against modern ones-was utterly overthrown. We may compare the Mahdi’s career with the ephemeral triumph of the Maccabees during the brief relaxation of pressure from Hellenism which the Jews enjoyed after the Romans had overthrown the Seleucid power and before they had taken its place; and we may infer that, as the Romans overthrew the Jewish ‘Zealots’ in the first and second centuries of the Christian era, so some great power of the Western world of today–Iet us say, the United States–could overthrow the Wahhabis now any time it chose if the Wahhabis’ ‘Zealotism’ became a sufficient nuisance to make the trouble of suppressing it seem worth while. Suppose, for instance, that the Sa’udi Arabian government, under pressure from its fanatical henchmen, were to demand exorbitant terms for oil concessions, or were to prohibit altogether the exploitation of its oil resources. The recent discovery of this hidden wealth beneath her arid soil is decidedly a menace to the independence of Arabia; for the West has now learnt how to conquer the desert by bringing into play its own technical inventions-railroads and armoured cars, tractors that can crawl like centipedes over sand-dunes, and aeroplanes that can skim above them like vultures. Indeed, in the Moroccan Rif and Atlas and on the north-west frontier of India during the inter-war years, the West demonstrated its ability to subdue a type of Islamic ‘Zealot’ who is much more formidable to deal with than the denizen of the desert. In these mountain fastnesses the French and British have encountered and defeated a highlander who has obtained possession of modern Western small arms and has learnt to a nicety how to use them on his own ground to the best advantage.

But of course the ‘Zealot’ armed with a smokeless quick firing rifle is no longer the ‘Zealot’ pure and undefiled, for, in as much as he has adopted the Westerner’s weapon, he has set foot upon unhallowed ground. No doubt if ever he thinks about it-and that is perhaps seldom, for the ‘Zealot’s’ behaviour is essentially irrational and instinctive he says in his heart that he will go thus far and no farther; that, having adopted just enough of the Westerner’s military technique to keep any aggressive Western power at arm’s length, he will consecrate the liberty thus preserved to the ‘keeping of the law’ in every other respect and will thereby continue to win God’s blessing for himself and for his offspring.

This state of mind may be illustrated by a conversation which took place in the nineteen-twenties between the Zaydi Imam Yahya of San’a and a British envoy whose mission was to persuade the Imam to restore peacefully a portion of the British Aden Protectorate which he had occupied during the general War of 1914-

1918 and had refused to evacuate thereafter, notwithstanding the defeat of his Ottoman overlords. In a final interview with the Imam, after it had become apparent that the mission would not attain its object, the British envoy, wishing to give the conversation another turn, complimented the Imam upon the soldierly appearance of his new-model army. Seeing that the Imam took the compliment in good part, he went on:

‘And I suppose you will be adopting other Western institutions as well?’

‘I think not,’ said the Imam with a smile.

‘Oh, really? That interests me. And may I venture to ask your reasons?’ ‘Well, I don’t think I should like other Western institutions,’ said the Imam. ‘Indeed? And what institutions, for example?’

‘Well, there are parliaments,’ said the Imam. ‘I like to be the Government myself. I might find a parliament tiresome.

‘Why, as for that,’ said the Englishman, ‘I can assure you that responsible parliamentary representative government is not an indispensable part of the apparatus of Western civilization. Look at Italy. She has given that up, and she is one of the great Western powers.’

‘Well, then there is alcohol,’ said the Imam, ‘I don’t want to see that introduced into my country, where at present it is happily almost unknown.’

‘Very natural,’ said the Englishman; ‘but, if it comes to that, I can assure you that alcohol is not an indispensable adjunct of Western civilization either. Look at America. She has given up that, and she too is one of the great Western powers.’ ‘Well, anyhow,’ said the Imam, with another smile which seemed to intimate that the conversation was at an end, ‘I don’t like parliaments and alcohol and that kind of thing.’

The Englishman could not make out whether there was any suggestion of humour in the parting smile with which the last five words were uttered; but, however that might be, those words went to the heart of the matter and showed that the inquiry about possible further Western innovations at San’a had been more pertinent than the Imam might have cared to admit. Those words indicated, in fact, that the Imam, viewing Western civilization from a great way off, saw it, in that distant perspective, as something one and indivisible and recognized certain features of it, which to a Westerner’s eye would appear to have nothing whatever to do with one another, as being organically related parts of that indivisible whole. Thus, on his own tacit admission, the Imam, in adopting the rudiments of the Western military technique, had introduced into the life of his people the thin end of a wedge which in time would inexorably cleave their close-compacted traditional Islamic civilization asunder. He had started a cultural revolution which would leave the Yamanites, in the end, with no alternative but to cover their nakedness with a complete ready-made outfit of Western clothes. If the Imam had met his Hindu contemporary Mr. Gandhi, that is what he would have been told, and such a prophecy would have been supported by what had happened already to other Islamic peoples who had exposed themselves to the insidious process of ‘Westernization’ several generations earlier.

This, again, may be illustrated by a passage from a report on the state of Egypt in 1839 which was prepared for Lord Palmerston by Dr. John Bowring on the eve of one of the perpetual crises in ‘the Eastern question’ of Western diplomacy and towards the dose of the career of Mehmed Ali, an Ottoman statesman who, by that time, had been governing Egypt and systematically ‘Westernizing’ the life of the inhabitants of Egypt, for thirty-five years. In the course of this report, Dr. Bowring records the at first sight extraordinary fact that the only maternity hospital for Muslim women which then existed in Egypt was to be found within the bounds of Mehmed Ali’s naval arsenal at Alexandria, and he proceeds to unravel the cause. Mehmed Ali wanted to play an independent part in in- ternational affairs. The first requisite for this was an effective army and navy. An effective navy meant a navy built on the Western model of the day. The Western technique of naval architecture could only be practised and imparted by experts imported from Western countries; but such experts were unwilling to take service with the Pasha of Egypt, even on generous financial terms, unless they were assured of adequate provision for the welfare of their families and their subordinates according to the standards to which they were accustomed in their Western homes. One fundamental condition of welfare, as they understood it, was medical attendance by trained Western practitioners. Accordingly, no hospital, no arsenal; and therefore a hospital with a Western staff was attached to the arsenal from the beginning. The Western colony at the arsenal, however, was small in numbers; the hospital staff were consumed by that devouring energy with which the Franks had been cursed by God; the natives of Egypt were legion; and maternity cases are the commonest of all in the ordinary practice of medicine. The process by which a maternity hospital for Egyptian women grew up within the precincts of a naval arsenal managed by Western experts is thus made clear.

HERODIANISM

This brings us to a consideration of the alternative response to the challenge of pressure from an alien civilization; for, if the Imam Yahya of San’a may stand for a representative of ‘Zealotism’ in modern Islam (at least, of a ‘Zealotism’ tempered by a belief in keeping his powder dry), Mehmed Ali was a representative of ‘Herodianism’ whose genius entitles him to rank with the eponymous hero of the sect. Mehmed Ali was not actually the first ‘Herodian’ to arise in Islam. He was, however, the first to take the ‘Herodian’ course with impunity, after it had been the death of the one Muslim statesman who had an- ticipated him: the unfortunate Ottoman Sultan Selim III. Mehmed Ali was also the first to pursue the ‘Herodian’ course steadily with substantial success-in contrast to the chequered career of his contemporary and suzerain at Constantinople, Sultan Mahmud II.

The ‘Herodian’ is the man who acts on the principle that the most effective way to guard against the danger of the unknown is to master its secret; and, when he finds himself in the predicament of being confronted by a more highly skilled and better armed opponent, he responds by discarding his traditional art of war and

learning to fight his enemy with the enemy’s own tactics and own weapons. If ‘Zealotism’ is a form of archaism evoked by foreign pressure, ‘Herodianism’ is a form of cosmopolitanism evoked by the self-same external agency; and it is no accident that, whereas the strongholds of modern Islamic ‘Zealotism’ have lain in the inhospitable steppes and oases of Najd and the Sahara, modern Islamic ‘Herodianism’ -which was generated by the same forces at about the same time, rather more than a century and a half ago-has been focused, since the days of Selim III and Mehmed ‘Ali, at Constantinople and Cairo. Geographically, Constantinople and Cairo represent the opposite extreme, in the domain of modern Islam, to the Wahhabis’ capital at Riyadh on the steppes of the Najd and to the Sanusis’ stronghold at Kufarii. The oases that have been the fastnesses of Islamic ‘Zealotism’ are conspicuously inaccessible; the cities that have been the nurseries of Islamic ‘Herodianism’ lie on, or close to, the great natural international thoroughfares of the Black Sea Straits and the Isthmus of Suez; and for this reason, as well as on account of the strategic importance and economic wealth of the two countries of which they have been the respective capitals, Cairo and Constantinople have exerted the strongest attraction upon Western enterprise of all kinds, ever since the modern West began to draw its net close round the citadel of Islam.

It is self-evident that ‘Herodianism’ is by far the more effective of the two alternative responses which may be evoked in a society that has been thrown on the defensive by the impact of an alien force in superior strength. The “Zealot’ tries to take cover in the past, like an .ostrich burying its head in the sand to hide from its pursuers; the ‘Herodian’ courageously faces the present and explores the future. The ‘Zealot’ acts on instinct, the ‘Herodian’ by reason. In fact, the ‘Herodian’ has to make a combined effort of intellect and will in order to overcome the ‘Zealot’ impulse, which is the normal first spontaneous reaction of human nature to the challenge confronting ‘Zealot’ and ‘Herodian’ alike. To have turned ‘Herodian’ is in itself a mark of character (though not necessarily of an amiable character) ; and it is noteworthy that the Japanese, who, of all the non- Western peoples that the modern West has challenged, have been perhaps the least unsuccessful exponents of ‘Herodianism’ in the world so far, were the most effective exponents of ‘Zealotism’ previously, from the sixteen-thirties to the eighteen-sixties. Being people of strong character, the Japanese made the best that could be made out of the ‘Zealot’s’ response; and for the same reason, when the hard facts ultimately convinced them that a persistence in this response would lead them into disaster, they deliberately veered about and proceeded to sail their ship on the ‘Herodian’ tack.

Nevertheless, ‘Herodianism,’ though it is an incomparably more effective response than ‘Zealotism’ to the inexorable ‘Western question’ that confronts the whole contemporary world, does not really offer a solution. For one thing, it is a dangerous game; for, to vary our metaphor, it is a form of swapping horses while crossing a stream, and the rider who fails to find his seat in the new saddle is swept off by the current to a death as certain as that which awaits the ‘Zealot’

when, with spear and shield, he charges a machine-gun. The crossing is perilous, and many there be that perish by the way. In Egypt and Turkey, for example–the two countries which have served the Islamic pioneers of ‘Herodianism’ as the fields for their experiment–the epigoni proved unequal to the extraordinarily difficult task which the ‘elder statesmen’ had bequeathed to them. The consequence was that in both countries the ‘Herodian’ movement fell on evil days less than a hundred years after its initiation, that is to say, in the earlier years of the last quarter of the nineteenth century; and the stunting and retarding effect of this set-back is still painfully visible, in different forms, in the life of both countries.

Two still more serious, because inherent, weaknesses of ‘Herodianism’ may be discerned if we turn our attention to Turkey as she is to-day, when her leaders, after overcoming the Hamidian set-back by a heroic tour de force, have carried ‘Herodianism’ to its logical conclusion in a revolution which, for ruthless thoroughness, puts even the two classical Japanese revolutions of the seventh and the nineteenth centuries into the shade. Here, in Turkey, is a revolution which, instead of confining itself to a single plane, like our successive economic and political and aesthetic and religious revolutions in the West, has taken place on all these planes simultaneously and has thereby convulsed the whole life of the Turkish people from the heights to the depths of social experience and activity.

The Turks have not only changed their constitution (a relatively simple business, at least in respect of constitutional forms), but this unfledged Turkish Republic has deposed the Defender of the Islamic Faith and abolished his office, the Caliphate; disendowed the Islamic Church and dissolved the monasteries; removed the veil from women’s faces, with a repudiation of all that the veil im- plied; compelled the male sex to confound themselves with unbelievers by wearing hats with brims which make it impossible for the wearer to perform the complete traditional Islamic prayer-drill by touching the floor of the mosque with his forehead; made a clean sweep of the Islamic law by translating the Swiss civil code into Turkish verbatim and the Italian criminal code with adaptations, and then bringing both codes into force by a vote of the National Assembly; and exchanged the Arabic script for the Latin: a change which could not be carried through without jettisoning the greater part of the old Ottoman literary heritage. Most noteworthy and most audacious change of all, these ‘Herodian’ revolutionaries in Turkey have placed before their people a new social ideal- inspiring them to set their hearts no longer, as before, on being husbandmen and warriors and rulers of men, but on going into commerce and industry and proving that, when they try, they can hold their own against the Westerner himself, as well as against the Westernized Greek, Armenian, or Jew, in activities in which they have formerly disdained to compete because they have traditionally regarded them as despicable.

This ‘Herodian’ revolution in Turkey has been carried through with such spirit, under such serious handicaps and against such heavy odds, that any generous- minded observer will make allowances for its blunders and even for its crimes and will wish it success in its formidable task. Tantus labor non sit cassus – and it would be particularly ungracious in a Western observer to cavil or scoff; for, after all, these Turkish ‘Herodians’ have been trying to turn their people and their country into something which, since Islam and the West first met, we have always denounced them for not being by nature: they have been trying, thus late in the day, to produce replicas, in Turkey, of a Western nation and a Western state. Yet, as soon as we have clearly realized the goal, we cannot help wondering whether all this labor and travail that has been spent on striving to reach it has been really worth while.

Certainly we did not like the outrageous old-fashioned Turkish ‘Zealot’ who flouted us in the posture of the Pharisee thanking God daily that he was not as other men were. So long as he prided himself on being ‘a peculiar people’ we set ourselves to humble his pride by making his peculiarity odious; and so we called him ‘the Unspeakable Turk’ until we pierced his psychological armor and goaded him into that ‘Herodian’ revolution which he has now consummated under our eyes. Yet now that, under the goad of our censure, he has changed his tune and has searched out every means of making himself indistinguishable from the nations around him, we are embarrassed and even inclined to be indignant-as Samuel was when the Israelites confessed the vulgarity of their motive for de- siring a king.

In the circumstances, this new complaint of ours against the Turk is ungracious, to say the least. The victim of our censure might retort that, whatever he does, he cannot do right in our eyes, and he might quote against us, from our own Scriptures: ‘We have piped unto you and ye have not danced; we have mourned to you and ye have not wept.’ Yet it does not follow that, because our criticism is ungracious, it is also merely captious or altogether beside the mark. For what, after all, will be added to the heritage of civilization if this labor proves to have been not in vain and if the aim of these thoroughgoing Turkish ‘Herodians’ is achieved in the fullest possible measure?

It is at this point that the two inherent weaknesses of ‘Herodianism’ reveal themselves. The first of them is that ‘Herodianism’ is, ex hypothesi, mimetic and not creative, so that, even if it succeeds, it is apt simply to enlarge the quantity of the machine-made products of the imitated society instead of releasing new creative energies in human souls. The second weakness is that this uninspiring success, which is the best that ‘Herodianism’ has to offer, can bring salvation- even mere salvation in this world-only to a small minority of any community which takes the ‘Herodian’ path. The majority cannot look forward even to becoming passive members of the imitated civilization’s ruling class. Their destiny is to swell the ranks of the imitated civilization’s proletariat. Mussolini once acutely remarked that there are proletarian nations as well as proletarian classes and individuals; and this is evidently the category into which the non-Western peoples

of the contemporary world are likely to enter, even if, by a tour de force of ‘Herodianism,’ they succeed outwardly in transforming their countries into sovereign independent national states on the Western pattern and become associated with their Western sisters as nominally free and equal members of an all-embracing international society.

Thus, in considering the subject of this paper-the influence which the present encounter between Islam and the West may be expected to have on the future of mankind-we may ignore both the Islamic ‘Zealot’ and the Islamic ‘Herodian’ in so far as they carry their respective reactions through to such measure of success as is open to them; for their utmost possible success is the negative achievement of material survival. The rare ‘Zealot’ who escapes extermination becomes the fossil of a civilization which is extinct as a living force; the rather less infrequent ‘Herodian’ who escapes submergence becomes a mimic of the living civilization to which he assimilates himself. Neither the one nor the other is in a position to make any creative contribution to this living civilization’s further growth.

We may note incidentally that, in the modern encounter of Islam with the West, the ‘Herodian’ and ‘Zealot’ reactions have several times actually collided with each other and to some extent cancelled each other out. The first use which Mehmed ‘All made of his new ‘Westernized’ army was to attack the Wahhabis and quell the first outburst of their zeal. Two generations later, it was the uprising of the Mahdi against the Egyptian regime in the Eastern Sudan that gave the coup de grace to the first ‘Herodian’ effort to make Egypt into a power capable of standing politically on her own feet ‘under the strenuous conditions of the modern world’; for it was this that confirmed the British military occupation of 1882, with all the political consequences which have flowed therefrom since then.

Again, in our time, the decision of the late king of Afghanistan to break with a tradition of ‘Zealotism’ which had previously been the keynote of Afghan policy since the first Anglo-Afghan War of 1838-42 has probably decided the fate of the ‘Zealot’ tribesmen along the north-west frontier of India. For though King Amanallah’s impatience soon cost him his throne and evoked a ‘Zealot’ reaction among his former subjects, it is fairly safe to prophesy that his successors will travel-:-more surely because more slowly -along the same ‘Herodian’ path. And the progress of Herodianism in Afghanistan spells the tribesmen’s doom. So long as these tribesmen had behind them an Afghanistan which cultivated as a policy that reaction towards the pressure of the West which the tribesmen themselves had adopted by instinct, they themselves could continue to take the ‘Zealot’s’ course with impunity. Now that they are caught between two fires-on the one side from India as before, and on the other side from an Afghanistan which has taken the first steps along the ‘Herodian’ path-the tribesmen seem likely sooner or later to be confronted with a choice between conformity and extermination. It may be noted, in passing, that the ‘Herodian,’ when he does collide with the ‘Zealot’ of his own household, is apt to deal with him much more ruthlessly than the Westerner would have the heart to do. The Westerner chastises the Islamic

‘Zealot’ with whips; the Islamic ‘Herodian’ chastises him with scorpions. The ‘frightfulness’ with which King Amanallah suppressed his Pathan rebellion in 1924, and President Mustafii Kemal Ataturk his Kurdish rebellion in 1925, stands out in striking contrast to the more humane methods by which, at that very time, other recalcitrant Kurds were being brought to heel in what was then the British mandated territory of ‘Iraq and other Pathans in the north-west frontier province of what was then British India.

To what conclusion does our investigation lead us? Are we to conclude that, because, for our purpose, both the successful Islamic ‘Herodian’ and the successful Islamic ‘Zealot’ are to be ignored, the present encounter between Islam and the West will have on the future of mankind no influence whatsoever? By no means; for, in dismissing from consideration the successful ‘Herodian’ and ‘Zealot,’ we have only disposed of a small minority of the members of the Islamic society. The destiny of the majority, it has already been suggested above, is neither to be exterminated nor to be fossilized nor to be assimilated, but to be submerged by being enrolled in that vast, cosmopolitan, ubiquitous proletariat which is one of the most portentous by-products of the ‘Westernization’ of the world.

At first sight it might appear that, in thus envisaging the future of the majority of Muslims in a ‘Westernized’ world, we had completed the answer to our question, and this in the same sense as before. If we convict the ‘Herodian’ Muslim and the ‘Zealot’ Muslim of cultural sterility, must we not convict the ‘proletarian’ Muslim of the same fatal defect a fortiori? Indeed, is there anyone who would dissent from that verdict on first thoughts? We can imagine arch-‘Herodians’ like the late President Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and arch-‘Zealots’ like the Grand Sanusi concurring with enlightened Western colonial administrators like the late Lord Cromer or General Lyautey to exclaim with one accord: ‘Can any creative contribution to the civilization of the future be expected from the Egyptian fallah or the Constantinopolitan hammal?’ Just so, in the early years of the Christian era, when Syria was feeling the pressure of Greece, Herod Antipas and Gamaliel and those zealous Theudases and Judases who, in Gamaliel’s memory, had perished by the sword, would almost certainly have concurred with a Greek poet in partibus Orientalium like Meleager of Gadara, or a Roman provincial governor like Gallio, in asking, in the same satirical tone: ‘Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?’ Now when the question is put in that historic form, we have no doubt as to the answer, because the Greek and Syrian civilizations have both run their course and the story of their relations is known to us from beginning to end. The answer is so familiar now that it requires a certain effort of the imagination for us to realize how surprising and even shocking this particular verdict of history would have been to intelligent Greeks and Romans and Idumaeans and Jews of the generation in which the question was originally asked. For although, from their profoundly different standpoints, they might have agreed in hardly anything else, they would almost certainly have agreed in answering that particular question with an emphatic and contemptuous ‘No.’

In the light of history, we perceive that their answer would have been ludicrously wrong if we take as our criterion of goodness the manifestation of creative power. In that pammixia which arose from the intrusion of the Greek civilization upon the civilizations of Syria and Iran and Egypt and Babylonia and India, the proverbial sterility of the hybrid seems to have descended upon the dominant class of the Hellenic society as well as upon those Orientals who followed out to the end the alternative ‘Herodian’ and ‘Zealot’ courses. The one sphere in which this Graeco Oriental cosmopolitan society was undoubtedly exempted from that course was the underworld of the Oriental proletariat, of which Nazareth was one type and symbol; and from this underworld, under these apparently adverse conditions, there came forth some of the mightiest creations

hitherto achieved by the spirit of man: a cluster of higher religions. Their sound has gone forth into all lands, and it is still echoing in our ears. Their names are names of power: Christianity and Mithraism and Manichaeism; the worship of the Mother and her dying and rising husband-son under the alternative names of Cybele-Isis and Attis-Osiris; the worship of the heavenly bodies; and the Mahayana School of Buddhism, which-changing, as it travelled, from a philosophy into a religion under Iranian and Syrian influence-irradiated the Far East with Indian thought embodied in a new art of Greek inspiration. If these precedents have any significance for us–and they are the only beams of light which we can bring to bear upon the darkness that shrouds our own future–they portend that Islam, in entering into the proletarian underworld of our latter day Western civilization, may eventually compete with India and the Far East and Russia for the prize of influencing the future in ways that may pass our understanding.

Indeed, under the impact of the West, the great deeps of Islam are already stirring, and even in these early days we can discern certain spiritual movements which might conceivably become the embryos of new higher religions. The Baha’i and Ahmadi movements, which, from Acre and Lahore, have begun to send out their missionaries to Europe and America, will occur to the contemporary Western observer’s mind; but at this point of prognostication we have reached our Pillars of Hercules, where the prudent investigator stays his course and refrains from at tempting to sail out into an ocean of future time in which he can take no more than the most general bearings. While we can speculate with profit on the general shape of things to come, we can foresee the precise shadows of particular coming events only a very short way ahead; and those historical precedents which we have taken as our guiding lights inform us that the religions which are generated when civilizations clash take many centuries to grow to maturity and that, in a race that is so long drawn out, a dark horse is often the winner.

Six and a half centuries separated the year in which Constantine gave public patronage to Christianity from the year in which the Hellespont had been crossed by Alexander the Great; five and a half centuries separated the age of the first

Chinese pilgrims to the Buddhist Holy Land in Bihar from that of Menander, the Greek ruler of Hindustan who put to Indian Buddhist sages the question: ‘What is truth?’ The present impact of the West on Islam, which began to make its pressure felt little more than a hundred and fifty years ago, is evidently unlikely, on these analogies, to produce comparable effects within any time that falls within the range of our powers of precise prevision; and therefore any attempt to forecast such possible effects might be an unprofitable exercise of the fancy.

We can, however, discern certain principles of Islam which, if brought to bear on the social life of the new cosmopolitan proletariat, might have important salutary effects on ‘the great society’ in a nearer future. Two conspicuous sources of danger one psychological and the other material-in the present relations of this cosmopolitan proletariat with the dominant element in our modern Western society are race consciousness and alcohol; and in the struggle with each of these evils the Islamic spirit has a service to render which might prove, if it were accepted, to be of high moral and social value.

RACIAL ISSUES

The extinction of race consciousness as between Muslims is one of the outstanding moral achievements of Islam, and in the contemporary world there is, as it happens, a crying need for the propagation of this Islamic virtue; for, al- though the record of history would seem on the whole to show that race consciousness has been the exception and not the rule in the constant inter- breeding of the human species, it is a fatality of the present situation that this consciousness is felt-and felt strongly-by the very peoples which, in the competition of the last four centuries between several Western powers, have won-at least for the moment-the lion’s share of the inheritance of the Earth.

Though in certain other respects the triumph of the English-speaking peoples may be judged, in retrospect, to have been a blessing to mankind, in this perilous matter of race feeling it can hardly be denied that it has been a misfortune. The English-speaking nations that have established themselves in the New World overseas have not, on the whole, been ‘good mixers.’ They have mostly swept away their primitive predecessors; and, where they have either allowed a primitive population to survive, as in South Africa, or have imported primitive ‘man-power’ from elsewhere, as in North America, they have developed the rudiments of that paralyzing institution which in India — where in the course of many centuries it has grown to its full stature-we have learnt to deplore under the name of ‘caste.’ Moreover, the alternative to extermination or segregation has been exclusion-a policy which averts the danger of internal schism in the life of the community which practices it, but does so at the price of producing a not less dangerous state of international tension between the excluding and the excluded races-especially when this policy is applied to representatives of alien races who are not primitive but civilized, like the Hindus and Chinese and Japanese. In this respect, then, the triumph of the English-speaking peoples has imposed on mankind a ‘race question’ which would hardly have arisen, or at least hardly in

15

such an acute form and over so wide an area, if the French, for example, and not the English, had been victorious in the eighteenth-century struggle for the possession of India and North America.

As things are now, the exponents of racial intolerance are in the ascendant, and, if their attitude towards ‘the race question’ prevails, it may eventually provoke a general catastrophe. Yet the forces of racial toleration, which at present seem to be fighting a losing battle in a spiritual struggle of immense importance to mankind, might still regain the upper hand if any strong influence militating against race consciousness that has hitherto been held in reserve were now to be thrown into the scales. It is conceivable that the spirit of Islam might be the timely reinforcement which would decide this issue in favor of tolerance and peace.

ALCOHOL

As for the evil of alcohol, it is at its worst among primitive populations in tropical regions which have been ‘opened up’ by Western enterprise; and, though the more enlightened part of Western public opinion has long been conscious of this evil and has exerted itself to combat it, its power of effective action is rather narrowly limited. Western public opinion can only take action in such a matter by bringing its influence to bear upon Western administrators of the tropical dependencies of Western powers; and, while benevolent administrative action in this sphere has been strengthened by international conventions, and these are now being consolidated and extended under the auspices of the United Nations, the fact remains that even the most statesmanlike preventive measures imposed by external authority are incapable of liberating a community from a social vice unless a desire for liberation and a will to carry this desire into voluntary action on its own part are awakened in the hearts of the people concerned. Now Western administrators, at any rate those of ‘Anglo-Saxon’ origin, are spiritually isolated from their ‘native’ wards by the physical ‘color bar’ which their race- consciousness sets up; the conversion of the native’s soul is a task to which their competence can hardly be expected to extend; and it is at this point that Islam may have a part to play.

THE FUTURE

In these recently and rapidly ‘opened up’ tropical territories, the Western civilization has produced an economic and political plenum and, in the same breath, a social and spiritual void. The frail customary institutions of the primitive societies which were formerly at home ill. the land have been shattered to pieces by the impact of the ponderous Western machine, and millions of ‘native’ men, women, and children, suddenly deprived of their traditional social environment, have been left spiritually naked and abashed. The more liberal- minded and intelligent of the Western administrators have lately realized the vast extent of the psychological destruction which the process of Western penetration has unintentionally but inevitably caused; and they are now making sympathetic efforts to save what can still be saved from the wreck of the ‘native’ social

16

heritage, and even to reconstruct artificially, on firmer foundations, certain valuable ‘native’ institutions which have been already overthrown. Yet the spiritual void in the ‘native’s’ soul has been, and still remains, a great abyss; the proposition that ‘Nature abhors a vacuum’ is as true in the spiritual world as in the material; and the Western civilization, which has failed to fill this spiritual vacuum itself, has placed at the disposal of any other spiritual forces which may choose to take the field an incomparable system of material means of communication.

In two of these tropical regions, Central Africa and Indonesia, Islam is the spiritual force which has taken advantage of the opportunity thus thrown open by the Western pioneers of material civilization to all comers on the spiritual plane; and, if ever the ‘natives’ of these regions succeed in recapturing a spiritual state in which they are able to call their souls their own, it may prove to have been the Islamic spirit that has given fresh form to the void. This spirit may be expected to manifest itself in many practical ways; and one of these. manifestations might be a liberation from alcohol which was inspired by religious conviction and which was therefore able to accomplish what could never be enforced by the external sanction of an alien law.

Here, then, in the foreground of the future, we can remark two valuable influences which Islam may exert upon the cosmopolitan proletariat of a Western society that has cast its net round the world and embraced the whole of mankind; while in the more distant future we may speculate on the possible contributions of Islam to some new manifestation of religion. These several possibilities, however, are all alike contingent upon a happy outcome of the situation in which mankind finds itself to-day. They presuppose that the discordant pammixia set up by the Western conquest of the world will gradually and peacefully shape itself into a harmonious synthesis out of which, centuries hence, new creative variations might again gradually and peacefully arise. This presupposition, however, is merely an unverifiable assumption which mayor may not be justified by the event. A pammixia may end in a synthesis, but it may equally well end in an explosion; and, in that disaster, Islam might have quite a different part to playas the active ingredient in some violent reaction of the cosmopolitan underworld against its Western masters.

At the moment, it is true, this destructive possibility does not appear to be imminent; for the impressive word ‘Pan-Islamism’-which has been the bugbear of Western colonial administrators since it was first given currency by the policy of Sultan ‘Abd-al-Hamid-has lately been losing such hold as it may ever have obtained over the minds of Muslims. The inherent difficulties of conducting a ‘Pan-Islamic’ movement are, indeed, plain to see. ‘PanIslamism’ is simply a manifestation of that instinct which prompts a herd of buffalo, grazing scattered over the plain, to form a phalanx, heads down and horns outward, as soon as an enemy appears within range. In other words, it is an example of that reversion to

traditional tactics in face of a superior and unfamiliar opponent, to which the name of ‘Zealotism’ has been given in this paper. Psychologically, therefore, ‘Pan-Islamism’ should appeal par excellence to Islamic ‘Zealots’ in the Wahhabi or Sanusi vein; but this psychological predisposition is balked by a technical diffi- culty; for in a society that is dispersed abroad, as Islam is, from Morocco to the Philippines and from the Volga to the Zambesi, the tactics of solidarity are as difficult to execute as they are easy to imagine.

The herd-instinct emerges spontaneously; but it can hardly be translated into effective action without taking advantage of the elaborate system of mechanical communications which modem Western ingenuity has conjured up: steamships, railways, telegraphs, telephones, aeroplanes, motor-cars, newspapers, and the rest. Now the use of these instruments is beyond the compass of the Islamic ‘Zealot’s’ ability; and the Islamic ‘Herodian,’ who has succeeded in making himself more or less master of them, ex hypothesi desires to employ them, not in captaining a ‘Holy War’ against the West, but in reorganizing his own life on a Western pattern. One of the most remarkable signs of the times in the contemporary Islamic world is the emphasis with which the Turkish Republic has repudiated the tradition of Islamic solidarity. ‘We are determined to work out our own salvation,’ the Turks seem to say, ‘and this salvation, as we see it, lies in learning how to stand on our own feet in the posture of an economically self- sufficient and politically independent sovereign state on the Western model. It is for other Muslims to work out their salvation for themselves as may seem good to them. We neither ask their help any longer nor offer them ours. Every people for itself, and the Devil take the hindermost, alIa franca!’

Now though, since 1922, the Turks have done almost everything conceivable to flout Islamic sentiment, they have gained rather than lost prestige among other Muslims -even among some Muslims who have publicly denounced the Turks’ audacious course-in virtue of the very success with which their audacities have so far been attended. And this makes it probable that the path of nationalism which the Turks are taking so decidedly to-day will be taken by other Muslim peoples with equal conviction tomorrow. The Arabs and the Persians are already on the move. Even the remote and hitherto ‘Zealot’ Afghans have set their feet on this course, and they will not be the last. In fact, nationalism, and not Pan- Islamism, is the formation into which the Islamic peoples are falling; and for the majority of Muslims the inevitable, though undesired, outcome of nationalism will be submergence in the cosmopolitan proletariat of the Western world.

This view of the present prospects of ‘Pan- Islamism’ is borne out by the failure of the attempt to resuscitate the Caliphate. During the last quarter of the nineteenth century the Ottoman Sultan ‘Abd-al-Hamld, discovering the title of Caliph in the lumber-room of the Seraglio, began to make play with it as a means of rallying ‘Pan-1slamic’ feeling round his own person. After 1922, however, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and his companions, finding this resuscitated Caliphate incompatible with their own radically ‘Herodian’ political ideas, first committed the historical

solecism of equating the Caliphate with ‘spiritual’ as opposed to ‘temporal’ power and finally abolished the office altogether. This action on the part of the Turks stimulated other Muslims, who were distressed by such highhanded treatment of a historic Muslim institution, to hold a Caliphate Conference at Cairo in 1926 in order to see if anything could be done to adapt a historic Muslim institution to the needs of a newfangled age. Anyone who examines the records of this conference will carry away the conviction that the Caliphate is dead, and that this is so because Pan-Islamism is dormant.

Pan-Islamism is dormant-yet we have to reckon with the possibility that the sleeper may awake if ever the cosmopolitan proletariat of a ‘Westernized’ world revolts against Western domination and cries out for anti-Western leadership. That call might have incalculable psychological effects in evoking the militant spirit of Islam-even if it had slumbered as long as the Seven Sleepers-because it might awaken echoes of a heroic age. On two historic occasions in the past, Islam has been the sign in which an Oriental society has risen up victoriously against an Occidental intruder. Under the first successors of the Prophet, Islam liberated Syria and Egypt from a Hellenic domination which had weighed on them for nearly a thousand years. Under Zangi and Nur-ad-Din and Saladin and the Mamliiks, Islam held the fort against the assaults of Crusaders and Mongols. If the present situation of mankind were to precipitate a ‘race war,’ Islam might be moved to play her historic role once again. Absit omen.

عباسی دور میں مسلمانوں کے اندر دین کا زوال آیا. اس دور میں مسلمانوں کا یہ حال ہوا کہ کچھ رسمی اعمال اور مخصوص وضع قطع دین داری کی علامت بن گئے. اسی زمانے میں قصہ خواں پیدا ہوۓ وہ ان رسمی اعمال کے پراسرار فضائل پر خود ساختہ کہانیاں لوگوں کو سننانے لگے. لوگ اس رسمی دین داری پر پختہ ہو گئے اور اپنا محاسبہ کرنے کا جذبہ ختم ہو گیا. موجودہ زمانے میں بھی ایسی شخصیات اور جماعتیں پیدا ہوئی ہیں جو لوگوں کو ایسے ہی خود ساختہ قصے سنا کر ان کے اندر محاسبے کا مزاج تو نہیں پیدا کرتےالبتہ فضیلت کی کہانیوں کی بدولت ان میں یہ فرضی یقین پیدا کر رہے ہیں کہ تمہاری رسمی دین داری ہی اصل دین داری ہے اور اسی کی وجہ سے تم خدا کی نصرت حاصل کرو گے اور آخر جنت میں پوھنچ جاؤ گے. یہ بلاشبہ گمراہی ہے، جو لوگ اس سے ناواقف ہیں وہ اندھے پن کا شکار ہیں اور جو واقف ہو کر خاموش ہیں وہ حدیث کے مطابق گونگے شیطان ہیں. موجودہ دور میں اصلاح امت کا سب سے بڑا کام یہی ہے کہ مسلمانوں کو اس گمراہی سے باہر نکالا جاۓ. پچھلی امتوں کے زوال کی وجہ جس چیز کو قرآن (سورۂ البقرہ آیت ٧٨) میں قرار دیا گیا ہے وہ یہی خوش فہمی ہے. جس کا مطلب ہے کچھ رسمی اعمال کرنا اور ان کے بدلے بڑے بڑے انعامات لینا. یہی پہلی قوموں کی تباہی کا سبب بنا اور حدیث کے مطابق یہی آخری وقت میں مسلمانوں کے زوال کی وجہ بنے گا.

از مولانا وحید الدین خان

“There is none amongst the believers who plants a tree, or sows a seed, and then a bird, or a person, or an animal eats thereof, but it is regarded as having given a charitable gift [for which there is great recompense].” [Al-Bukhari, III:513]

The idea of the Prophet Mohammed (SAW) as a pioneer of environmentalism will initially strike many as strange: indeed, the term “environment” and related concepts like “ecology”, “environmental awareness” and “sustainability”, are modern-day inventions, terms that were formulated in the face of the growing concerns about the contemporary state of the natural world around us.

And yet a closer reading of the hadith, the body of work that recounts significant events in the Prophet’s life, reveals that he was a staunch advocate of environmental protection. One could say he was an “environmentalist avant la lettre”, a pioneer in the domain of conservation, sustainable development and resource management, and one who constantly sought to maintain a harmonious balance between man and nature. From all accounts of his life and deeds, we read that the Prophet (SAW) had a profound…….connection to the four elements, earth, water, fire and air.